The Himalayan region’s glaciers represent the world’s largest reserve of fresh water outside of the North and South Poles. During the critical monsoon dry season (Nov-Apr), 1.3 billion people in Asia are dependent on 10 river systems flowing from this vast reserve of water. Systematic glacier volume decreases across the region have been observed since 1975. According to a Nature study published in 2010, between 2003 and 2009, Himalayan glaciers lost an estimated 174 gigatonnes of water and 9% of overall volume since the 1970s.

Andrew Peters, associate member of The Explorer’s Club and his two children, Marisa (15) and Kevin (13) and wife Mei Ling recently returned from southwest China where they cooperated with Professor Tandong Yao of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in studying Yulong Mountain, home of one of the Himalaya’s southernmost glaciers.

The team wanted to take water flow readings from glacier streams that had direct impact on villages dependent on water for crop growth during the hot dry season and specifically chose April, as it is the end of the dry season. In 2019 around Yulong mountain most villages had not received even a centimeter of rain in the past two months and were entirely dependent on glacier runoff for drinking water and for crop irrigation.

Wenhai Glacier Bed

April 2019 Dry Fields

Abandoned Terraces

The areas of Wenhai and Baishuihe showed initial findings of decreased year-over-year water volume from the 36 readings taken on the expedition. Ongoing collaboration with Professor Tandong Yao will allow comparison with longer-term trends and other mountains in the immediate vicinity.

The team used two Geopack advanced flow meters, which measured to a precision of 1/1000th m/s and recorded the GPS coordinates and the inputs to an equation to derive the volume of water flowing over time.

In conversations with local people dependent on glacier water, we found a surprising range of responses to recent drier conditions. Some said that they were converting to hardier crops, such as potatos, while others said they are reducing their herd sizes. The dry conditions, particularly in the Wenhai region, were evident in the large number of abandoned terrace fields that previously would have been meticulously maintained to capture rain and glacier melt for growing crops.

Professor Tandong Yao of the Chinese Academy of Science

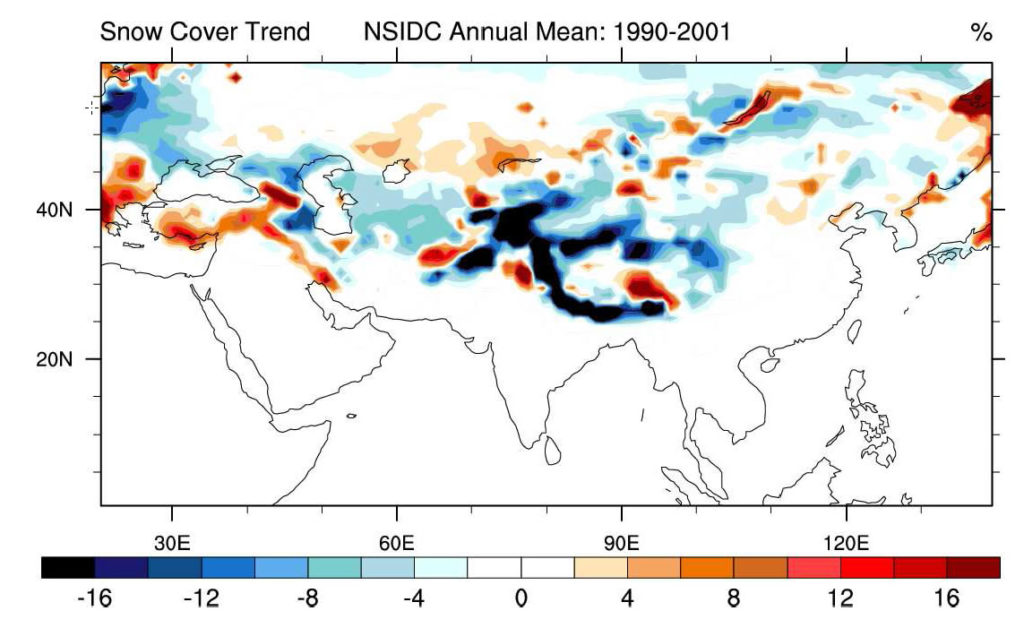

Snow Cover Trend 1990-2001